Third-Generation Leadership

Jean Bartell Barber, granddaughter of the company’s founder, George H. Bartell, Sr., serves as vice chairman and treasurer of Bartell Drugs, with responsibility for finance, risk management, human resources, real estate, construction, and strategic planning. Over the past seven years, Barber has also spearheaded the Executive Training Program at Bartell Drugs, which trains employees for executive-level positions within the company.

Jean Bartell Barber, granddaughter of the company’s founder, George H. Bartell, Sr., serves as vice chairman and treasurer of Bartell Drugs, with responsibility for finance, risk management, human resources, real estate, construction, and strategic planning. Over the past seven years, Barber has also spearheaded the Executive Training Program at Bartell Drugs, which trains employees for executive-level positions within the company.

Prior to becoming vice chairman, she was CFO of the company for nine years and spent an additional six years dealing primarily with risk management, property/casualty insurance, and computer management. She began her career while a teenager as did her brother and father before her, learning about the family business, taking store inventories, and working at the chain’s old Triangle store in downtown Seattle as a cashier clerk.

Barber graduated magna cum laude from the University of Washington with a bachelor of arts degree in business administration, and she graduated with distinction from The Wharton School’s MBA program at the University of Pennsylvania. She went on to become assistant vice president of the balance sheet management department at North Carolina National Bank (now Bank of America) and the treasurer of a home building business in North Carolina before moving back to Seattle to continue her involvement in the family business.

Barber is a member of the Executive Advisory Council of Seattle Pacific University and sits on the board for their Center for Integrity in Business. She is also a board member of the YWCA of King and Snohomish Counties. In 2008-09, she was co-chair of the Alaska Yukon Pacific Blue Ribbon Task Force for the city of Seattle.

This Conversation took place between Jean Bartell Barber and Al Erisman in the Bartell corporate office on the south side of Seattle on Monday, March 26, 2012, and was updated in early July 2012.

This article appears as an illustration of a successful family business in "The perils of inherited authority (1 Samuel 1-3)" in Samuel, Kings & Chronicles and Work at www.theologyofwork.org.

Ethix: How did you end up in this position in the family business?

Jean Barber: I started my career in banking with SeaFirst. I went through their management training program and ended up in the arm of the bank that participated in loans with smaller banks in the Pacific Northwest. After three and a half years, I went to Wharton to get my MBA, because there were opportunities I wanted to pursue that were not open to me without this degree. I came back to SeaFirst in one of those jobs, where I did liquidity analysis for the bank.

Then I got married, and moved to North Carolina and to the North Carolina National Bank doing something similar. They were the first bank to test interstate banking. They bought one tiny little bank in Florida to test the idea and then they bought two other larger banks in Florida. I was hired to do the financial analysis on the Florida operations.

It was a great opportunity, because the Florida banks didn’t have very good systems, so I largely had to rely on myself to do projections rather than on specific data. In the process, I became the person who understood how the Florida banks operated and were affected by the economics. Their banking environment was totally different from the North Carolina bank. This led to times at that early career stage where I was able to meet with the CEO and the CFO and explain to them why the Florida bank was operating the way it did. That was a fun job.

Three years later, however, my husband’s business took him to Durham, North Carolina, and then to Seattle. During that period, I worked in his business. After returning to Seattle, we had children and I took some time off when they were small. Then I started looking for something I could do part time, and took a position with the family business, Bartell Drugs, working about half time.

I had always felt I would not work for the family business, because I didn’t want to work for my older brother. If he wanted it, the business was his, and I didn’t want to be just his employee. But when I came back, I brought a lot of experience and we’ve got to be much more of a partnership, so it was a different situation. I started doing insurance purchasing, and then started the IT department when we first got into computers. It just went from there.

Family Business History

Tell us a bit of history about the family business.

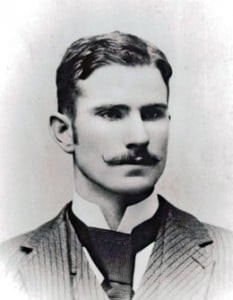

The first drug store was started by my grandfather in 1890. My brother and I are only the third generation of leaders in 122 years.

It started with just one store. He was a pharmacist by apprenticeship. He’d actually worked in a pharmacy for two weeks when he purchased the store from the doctor who had it. Back then, it wasn’t uncommon for a doctor to have his medical practice and then a pharmaceutical practice on the side. But the doctor found that it was too much and he needed to hire a pharmacist. My grandfather purchased the business from him very quickly on credit at age 21.

It started with just one store. He was a pharmacist by apprenticeship. He’d actually worked in a pharmacy for two weeks when he purchased the store from the doctor who had it. Back then, it wasn’t uncommon for a doctor to have his medical practice and then a pharmaceutical practice on the side. But the doctor found that it was too much and he needed to hire a pharmacist. My grandfather purchased the business from him very quickly on credit at age 21.

He had come out to Seattle about three years before on a horse train. His father came out for a visit a year or two after he had purchased the drug store and found out his son was in debt. He paid off the debt, and said, “I don’t want to hear you’re ever in debt again.” So that’s how he got his first store. He had just the one store when he went up to the Alaska Gold Rush in the mid-1890s, and came back with a plan to take advantage of the growth in Seattle that was happening at that time. His second store was located where the Smith Tower is today.

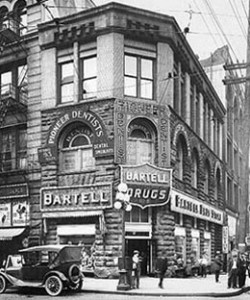

The first store was on Jackson Street in the International District located on a trolley line. It was just a year after the great Seattle fire, so downtown Seattle was a little bit in flux! This was probably why he ended up in Jackson Street to begin with. Then he just started steady growth from there with mainly downtown stores. He opened a store in the early 1920s in the University District, with a store in Ballard when Ballard was still a separate town, but most of them were downtown.

The first store was on Jackson Street in the International District located on a trolley line. It was just a year after the great Seattle fire, so downtown Seattle was a little bit in flux! This was probably why he ended up in Jackson Street to begin with. Then he just started steady growth from there with mainly downtown stores. He opened a store in the early 1920s in the University District, with a store in Ballard when Ballard was still a separate town, but most of them were downtown.

By 1930, we probably had about 20 stores, but back then they tended to be pretty small, full-service, old-fashioned drugstores. The growth continued. It probably slowed down in the ’30s, because of the Depression and then, of course, came to a grinding halt with World War II, which was probably the hardest event for the company to get through. It was much worse than the Depression. A lot of employees went off to war. We had some Japanese employees, who were interned. My dad, who was working for the business at that time, went off to war and so the management of the company was left with my grandfather and his management team. They were all in their 70s by then.

But the biggest problem is that consumer goods took a backseat to the war effort, and so a lot of consumer goods weren’t being manufactured anymore. So we didn’t have the goods to sell. Transportation was also disrupted, because of the war effort. Even after the war ended, it took a while for those things to get going again, and then the federal government put in, not only price controls, but profit controls. Most people don’t know that but there were caps on how much money you could make based on what you made in the prior year or two.

By now, my grandfather was 80 and still in the business, very typical of an entrepreneur. He didn’t really want to give up control until the day he died, and that had a huge effect, because he also kept his old cronies in place. People who’d worked for the company for 40 years were still running the company with him, and all that was pretty hard.

At the same time right after World War II, retail began to change, going to a more suburban, car-friendly self-service format that we know today. That was a huge shift. We had these now obsolete stores with employees who were used to doing business the old way. It was full-service with all of the merchandise behind the counter and owners in their 80s. That’s not an age where people are ready to try new things.

I just read recently that Wal-Mart, Kohls, and Target all started in 1965 after much of this change had happened. That’s also when Pay ‘N Save got its start, and for many of our years, was our chief competitor here in Seattle.

After my grandfather passed away and my father finally took over the management team, he felt he needed to take us to the next level. He started by closing some of the smaller, older stores and we were down to about 12 stores. Then he started opening larger suburban-type stores with parking lots. Today, we have 58 stores.

Transitions

How did the transition from your father to your brother and you go? Was that equally challenging?

The transition officially between my father and my brother happened in 1990; although, in a lot of respects, my brother was already running things by then. But it was important for my father to be able to say that, for the first 100 years of the company, it had only two presidents; so that’s why the changeover happened in 1990.

My father was not the entrepreneur. He was the caretaker-type person, which is typical second generation. He was not the dynamic go-getter that his dad had been and so that transition was much easier. You didn’t have the ego of the entrepreneur to deal with on the transition.

How do you see the next transition going? Are you anticipating that?

We’re trying to. I laughingly tell people that we Bartells were never quick to the altar or quick to the delivery room. It’s catching up to us because the next generation is ages 15 to 25 right now, so there’s going to be a gap. We’re going to need some outside management for a while, for the first time in our history.

We started bringing the kids in when they were 12 for a little bit of introduction to the company and then summer jobs when they were in high school. The eldest of the next generation, my daughter, did do a one-year job here after she graduated from college to get exposure to what it would mean if she ever did come to the company. But my brother had never worked anywhere but Bartell and I don’t think that’s the way to go.

I think it’s really important to get experience somewhere else, see how someone else does things, and so I’ve told my kids that they’re not working for the company unless they have experience somewhere else. So she is now employed elsewhere, as is my son. They are the two eldest of the next generation.

Keys to a Family Business

Do you know many family-owned businesses that have gone through three generations? Is this a common thing?

No, usually it’s very hard to get to the third generation – there's the old phrase “rags to riches to rags in three generations.” There are some, but most companies that are as old as us are on their fourth or fifth generation, which makes it that much harder.

The other thing that’s helped us is we’re a pretty small family. My grandfather just had a daughter and my father. My father bought his sister out at some point in the ’60s and so he controlled the company. So he was really almost like another entrepreneur in the sense that he was the only owner.

Then there were just the three of us. We bought my younger brother out 10 or 12 years ago. So, here we are in the third generation and there’s just the two of us who are the owners, and among us we have five kids. So, again normally, after 122 years, you’d had a family that had 50 members.

Going Public?

By being a private company you have different strengths and weaknesses compared to being a public company. How do you view that? Have you thought about becoming a public company?

No. We would never become public – that’s my feeling. I think we would sell before we’d ever become public, especially in today’s world with Sarbanes-Oxley and all those things. Being a public company would require us to deal with many laws that would make management difficult. Further, there are some great things about being private. We don’t have to have a short-term focus on quarterly profits. If we want to have a year or two where we’re reinvesting in the company and not making as much money, we can do that. This is very important to the health and the culture of the company.

What’s special about your company beyond being private and its family origin?

Family-owned obviously is a huge thing. But we’ve also been very conservative in the way we handle our money. We have very little debt. We finance all of our growth internally, not by debt. So when we hit things like the Depression or the Great Recession, we have a financial strength to weather those things. Companies that have been more aggressive in their growth perhaps are less able to weather those events.

In the ‘50s and the ‘60s, we were not very profitable. We’d make money one year and lose it the next year. But because we were private and a family company, we could weather those times and take the time we needed to make changes. That has been important.

I also think we’ve done a good job of maintaining the culture of our company, knowing what Bartell stands for. We have an emphasis on the golden rule and things like that. Culture is very important to the business. One reason why we have so many employees who worked for us from 20 or 30 or 40 years is because they feel valued and they feel like they are part of the family. They enjoy the fact they can see the owners, who are visible in the stores.

Expansion?

Have you thought about going to California or to the Midwest or anywhere out of the area?

No, we find we’re most successful when we locate in an area where our brand is known. Our brand is at its strongest right in the core, and I think if we were to go outside the area, we would have to start from scratch trying to explain to the people in the new area what our brand is. We haven’t felt the need to do that.

Seattle and Puget Sound is robust enough as an economy that we have found that we’ve had growth opportunities where we are. It means we can service all of our stores from one distribution site. It means the executives of the company can get into all the stores without taking road trips, and that’s important.

Company Culture

Tell me about the culture and how you deal with employees, how you deal with customers. What do you think is special about Bartell in that way?

We do our best to have a service mentality. The verb in our mission statement is “to serve,” and that’s who we are. We emphasize customer service ad nauseam, and we try to treat our employees as we would want to be treated. We want them to treat our customers the same way, and we feel, if we treat our 1,700 employees well then they, in turn, are going to treat our customers well. Do we do it 1,700 times? Well, we try.

Can you give me an example of the way you treat employees that might be a little different than other companies? Any stories?

I had someone call me up, just a clerk from one of our stores, and she had a friend who is a banker who was trying to emigrate from another country. I put her in contact with some people in banking that I knew who could maybe try to help her. I don’t think most people would feel like they could call the vice chairman of a company up and ask her a question like that and be able to have that person help them out.

The way we treat employees is reflected in how they treat customers. As an example, we had a pharmacist who knew a customer needed a prescription quickly and he actually met the customer’s evening train in order to deliver the prescription.

We have a policy that if you can’t get to your place of work, because of weather, you can go to another place of work and put in hours. So we have had people who work in the office go to a store to work their hours during a snowstorm, because they couldn’t get to their office. In 1996, during another bad snowstorm, we had a store in a leased facility where the roof collapsed. Fortunately, no one was there when that happened, but no one from that store could go into that place to work for a time. We simply had them go to a different store.

If you have business-interruption insurance, they usually expect certain expenses to stop when your business is interrupted. You’re not going to be paying rent in a situation like that, you’re not paying utilities, and you’re not paying tax and credit card fees. Insurance companies expect that most of your payroll stops too, particularly for hourly people. We have a standard policy with our insurance companies but that’s not the way Bartell does business. Even though a store might be down for over 90 days, we use people in other stores if at all possible. If we had an actual job opening, then we paid for that person, but if we didn’t have an opening then they were an extra on the payroll. The insurance company paid for that as part of our business interruption, because we insisted that this is the way we do business. Even a store manager will be placed in another store.

How do you get this service mentality down to the last employee? When you hire a middle employee, how do they learn that this is the Bartell way?

We have to rely on our store personnel to do most of it. Obviously, our HR department tries to start that process with our new-employee orientation, but we have to rely on our managers to inculcate that. But we have contests sometimes. We have customer-comment cards in all our stores, so they can tell us stories. We have a monthly newsletter where we tout great customer service both from the front of the store and the pharmacy. We have secret shoppers and we publish in our internal newsletter every employee who gets a “Wow” shop. At certain times of the year, we also have drawings. Every month, everyone who got a “Wow” has their name in a hat, and somebody wins a cash prize.

Dealing With Acquisitions

Have you grown through acquisition? Have you bought out other stores?

Not too much. Our biggest acquisition happened in the 1980s when we purchased the U.S. operations from Canada’s Shoppers Drug Mart. They had come to Washington and put in a few stores in the ’70s. We were in communications with them at that time to see if we would sell to them. We said “no” but put together an agreement that, if either of us were to sell, we would let the other party know. At some point, they decided that they wanted to just stay in Canada, so we purchased their stores here. That’s how we first got into Snohomish County.

How did you work the transition of the employees who have grown up in one culture to move them into another culture?

I was in North Carolina when that happened. But we have done a few acquisitions, one at a time, since then. We purchased an independent drug store in Bellevue, for example. We go in just like they are new employees. We do the new-employee orientation. We often put Bartell’s management in the store so they can start making sure that people are transitioned to our way of doing business. I suppose there have been occasional times when we interview somebody at an operation and decide they’re not a Bartell’s employee and don’t offer them a job. But that would be rare. Usually we give people a chance.

Pharmacy Challenges

The pharmacy world has changed a lot over the past few years. How have you dealt with that change?

That is a very good question. Yes, pharmacy is horrible. With all that’s been happening in managed health and the pharmaceutical industry, it’s a very trying time. Reimbursement rates have gone down significantly in the last few years, well over 10% on profit margins.

Pharmacy benefit management (PMB) companies are very difficult to deal with; they are not transparent. They are the companies that work with insurance companies, so they are the middlemen. We are forced to sign contracts where every year the contract actually says, “We’re going to pay you this this year, and next year we’re going to pay you less, and the year after that we’re going to pay you less.” So, it’s very difficult to make money on prescriptions. Some prescriptions we do not even make money on a gross profit basis.

Pharmacy benefit management (PMB) companies are very difficult to deal with; they are not transparent. They are the companies that work with insurance companies, so they are the middlemen. We are forced to sign contracts where every year the contract actually says, “We’re going to pay you this this year, and next year we’re going to pay you less, and the year after that we’re going to pay you less.” So, it’s very difficult to make money on prescriptions. Some prescriptions we do not even make money on a gross profit basis.

In addition, prior to the Great Recession, we had a huge pharmacist shortage nationally, with over 5,000 too few pharmacists in the United States. Because of this, pharmacist salaries skyrocketed 10 years ago. Your key employees are becoming very expensive at the time your reimbursements are getting smaller and smaller. For years, we couldn’t run our business the way we wanted to, because of the pharmacist shortage. We weren’t free to fire employees who weren’t giving the customer service we wanted, because we weren’t sure we could find somebody better to take their place.

There’s a huge consolidation in the PBM world going on right now. There is a big pending merger of Medco and Express Scripts. If it goes through, if the SEC agrees to it, they will have over 60% of the market. We as retailers have no choice but to do business with them, because how can you say “no” to 60% of the market? Walgreens has taken a stand and in the last year refused to sign a new contract with Express Scripts, because of the reimbursement Express Scripts was offering. Express Scripts probably has around 20% of the market or whatever. If they merge with Medco, I don’t know what Walgreens is going to do about that.

The other big PBM is owned by CVS. CVS is not in this market, but it’s as big as Walgreens nationally. That is a huge issue for a lot of us, because CVS would receive information about retailers through their PBM. If CVS were in this market and we were doing business with Caremark, then Caremark would know how many prescriptions we are filling for them in each store. Could they give that information to CVS’ retail business? “Well, this is the neighborhood you should be in, because this is the script count that Bartell has in that neighborhood.”

Are there any protections for you there?

Not that I know of, no. We have talked with other regional drugstore chains that have had real difficulties with this issue. A significant amount of their business goes through Caremark, who basically tell their customers, “As a Caremark customer, you must go to CVS to get that filled.”

The role of the pharmacist is very important, more so than many people realize. I have had a minor medical issue that eight different doctors have been unable to solve. On the advice of a friend, I went to the pharmacist at Bartell and described my problem to her, and she said, “Well, why don’t you try this off-the-shelf product.” Very helpful.

Yes, they do play an important, and often unappreciated role in health care. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work this well. We usually try to go out of our way to help people. Someone recently came into the store with relatives from out of state who had forgotten their meds. We worked with them to get their prescriptions filled. You cannot open up a pharmacy if you don’t have a pharmacist. There are times, because of illness or holiday schedules, that we have to use a service to get a pharmacist into a store. Maintaining the level of service is not always possible with a temp, but fortunately these situations are rare.

Some of your competitors are open 24 hours a day in their pharmacy. Are you doing that or are you planning to do that?

We had the first 24-hour pharmacy in this region and it’s still there. We now have one on the east side of Lake Washington and one on the west side. Twenty-four hour pharmacies are not profitable and so we do not put them in as widespread as Walgreens. Walgreens has a plan where they open almost every store as a 24-hour pharmacy, and then they’ll quietly get rid of the hours.

I read in one of your histories that your grandfather was actually the first 24-hour pharmacy.

That’s correct. He lived behind the pharmacy and was available to handle calls at any hour. It seems like we have come full circle.

Online Competition

Another competitor is online medication services. What is your response to that?

There’s a reason why you may want to talk with a pharmacist, as we discussed earlier. A different problem with an online or mail-order pharmacy is that it’s more difficult to manage your medications. For those who used to get all of their medication services at Bartell, your pharmacist would know about all of your prescriptions. If doctor A has prescribed something and doctor B prescribes something that conflicts with it, your pharmacist will catch it and warn you that you can’t take both those medications at one time. But if you’re getting medicine A through mail order and you come in with a new prescription to Bartell’s for B, we don’t know that A exists. We can’t warn you about an interaction that might be happening. There are other medications, for example, that you shouldn’t be taking with vitamin D. If there is some interaction with something that you might be using over the counter, are you going to get counsel if you’re getting that medicine online?

There are a lot of employers in this region that require people to call their mail order after 30 days and we just deal with it. But 2011 was the first year that mail-order pharmacy was flat since it got started. I believe you’re going to see it starting to go the other way, and more and more people are going to be offered the ability to go back to a drug store. Online growth was encouraged, though it was less convenient for many people. It took off when the brand-name drug manufacturers gave the mail-order companies the ability to purchase those drugs cheaper than retail. There’s a tier pricing, so hospitals and mail order get preferential pricing compared to anybody at retail. So then, if they had cheaper pricing, they could pass some of that on to employers, and that’s why so much went to mail order.

Eighty-five percent of prescriptions now are generic and there’s no tiered pricing except by volume. It’s a different model now, with less incentive to use mail order.

Beyond the Pharmacy

What is the breakdown in your business between pharmacy and other things?

We’re about 50-50, which is very unusual. Most of the market, for example Rite Aid, is about 65% pharmacy. It is not that we don’t have a strong pharmacy, we have a much stronger front-end compared to the competition.

When I walk into a Bartell’s, I observe that there are a lot of “food specials.” I know that my wife checks your ads each Monday for the specials you are offering. How does that fit with your strategy?

Throughout our history, we’ve been known for our strong ads, which include food items specifically purchased for our ads. We do have a basic offering of food that you’re going to find any time, but most of it is an ad purchase for something you’re only going to see when it’s in our ad.

We were having a business meeting with a company out of Texas. Before they came to our office, they went into a Bartell’s partly to check us out. The other reason was that one of the men lost his luggage on the trip to Seattle and needed a tie. They were laughing, because they got this tie for $5 at one of our stores. They also noticed that we had Blue Diamond almonds on our display. We have this great program with Blue Diamond, and these businesspeople were just blown away by the price. One of them said, “I’ve never seen that good a price in the grocery store, and so I’m going to have to go back and fill my suitcase with Blue Diamond almonds before we get on the plane again.” But we sell a lot from our ad and, therefore, we can get very good pricing from the distributor.

Technology Impacts

We’ve talked about the online pharmacies, but how else has technology affected your business?

Everything is automated. We have a warehouse that’s totally automated. We have handheld computers with sensors that you put on your finger that allow you to just point at a barcode in the warehouse and it instantly calls that up on your device. The pharmacy runs on auto ordering so that, when you get low on a particular drug, it will auto order it for you.

Credit-card transactions are also changing. In some parts of the world, some people now have their credit card in their phone, and simply having the phone near the machine allows you to complete a transaction, a “touch and go” system. We also have a new pharmacy computer system that gives us much better functionality and reporting. It also does workflow, allowing us to find out how long it is taking Al to get his prescription filled or help in making sure that we don’t make a mistake. It just seems like we turn around and there’s some new IT-related products.

It used to be that the photography area was big and now it’s very different. How have you handled with that?

We were early into photography, way back at the start of the 20th century. We used to have guaranteed two-hour delivery of prints. We had our own print studio where we processed film from people who had their old Brownie cameras. We used to deliver to our stores via motorcycle.

But digital photography changed all of that. Early into the digital era, we had two of the first digital kiosks on the first shipment from Japan.

How did that happen? Do you have a systematic way of looking for future trends?

My brother was the one who recognized this change in the market. He said, “We have to be into this market early, because it’s such a key component of our business.” We ordered the kiosks and then thought through how people would want to effectively use them. If you come into Bartell’s and you want to enhance a photo or if you want to get rid of the red eye, if you want to change the brightness, and all those things, you can do that at one of our kiosks. We thought that important. For many of our competitors, this personal interaction with the image is not available to the customer.

The other thing that we’ve done was provide customer service in this area. Some of our customers are not tech-savvy and are intimidated by the technology for creating prints. We don’t like to do that to our customers. If anyone has trouble, we will help them with their prints. I don’t think anyone else in the market does it like we do. We will sit there and help them use these tools as a part of our service. That helped us maintain our camera department better than some other places.

But that market has been going down about 25% per year. So, while we do a lot better than anyone else, we wish we were doing better. It used to be you would come to Bartell’s twice; once to leave your film, and once to pick them up. This gave them an opportunity to shop in between while they were waiting. Now it is all one step.

Why would someone come into your store to get prints now that the comparable technology is available at home?

In addition to the support we provide, you also get 100-year paper for your prints. Most people don’t realize the pictures they print at home will probably fade in 20 years. Something carefully printed in our store will be fine after 50 years.

Government Regulations

Let’s shift gears and talk a little bit about government regulations and how they affect your business. Let’s start with the privacy issues covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Good old HIPAA. HIPAA is a real pain. We actually have a full-time employee whose sole job is managing HIPAA. HIPAA came about because there were some companies that didn’t treat their customer information the way they should have, and that’s a problem. One has to be very careful, as we always have been, with customer data. Yet, I think most people find HIPAA to be more an annoyance than anything else, because of the bureaucracy it creates.

Here is an example: on a very rare occasion, somebody will get the wrong prescription. Say you’re John Doe and there is also a Joe Doe, and maybe we picked up the wrong prescription bag and we don’t notice so you walk out to your car. Then you look at it and go, “Wait, this is Joe Doe’s prescription. This isn’t mine.” You come back. “Hey, wait a minute. This is Joe’s, not John’s,” and we give you the right one. That’s a HIPAA violation, because you have seen Joe’s prescription.

If you have a 13-year-old daughter, you can’t get her records, because she might have ordered birth-control pills without your knowledge. We are not allowed to give you her records. So we have parents who come in and want to get a copy of the records for their 12-year olds or something, because they need it to get to a new doctor or they need it for another reason, and they can’t get those without their children’s consent. That makes a lot of people pretty upset, because they think, as a parent of a 12-year old, they should be able to get that information.

These are the things that make it difficult to deal with HIPAA. The reason for it made sense. People were selling prescription records to third parties for mass mailings and things like that. It makes sense to keep that from happening. Your prescription should not be public information. Like any regulation, though, it just goes too far.

From a regulator's point of view, when they see the abuses, they believe they need to do something to stop them. This is in essence what Susan Collins (R senator from Maine) said to me after the passing of Sarbanes-Oxley. They passed an imperfect law, but they had to do something. It seems like a lot of regulation happens that way. What would you do in their situation?

I’m not going there! But it creates a very difficult environment for running a business. Here’s another example. We have PCI, the privacy act around credit cards. It’s ridiculous what we have to do, and very, very expensive from an IT standpoint. With HIPAA, we have to keep records for multiple years. With PCI, we do not store any credit-card information and yet we have very strict guidelines on what we’re allowed to do, what we’re not allowed to do, and how this system has to stay separate from that system. No doubt, companies have lost credit-card information and that has given rise to these regulations. But it just gets to be so onerous, particularly when you’re a company our size. It’s going to cost us as much money to try to keep our systems safe as another company with 5,000 stores. That’s the biggest concern and what makes it so hard. We never get rid of an old regulation; new ones just keep getting layered on.

And it’s not just federal regulations. The city of Seattle now is requiring that any store we put in has to have a seven-foot vestibule to reduce energy-cost supposedly. But that’s going to be a huge expense on retail going forward, because of the space the vestibule is going to take. They pass that without any input from those who are affected by the law. There is a mandatory sick-leave ordinance that requires us to give everybody nine days of sick leave on top of all their other benefits. All of this comes from the city of Seattle. The bag ordinance, banning plastic bags in the city of Seattle, is the latest one. There are so many different regulations we must deal with.

Health Care Legislation

What about the health-care legislation? How does that affect you?

We don’t fully know its affect yet. We already have a very good health-care plan, but what they passed was really blue-ribbon health care. If you want to hold on to your own program, then you can’t make any changes to it.

We know it is going to increase our costs. For example, we don’t have mental-health parity in our plan. Well, the federal government has mental-health parity in their plan, so we have to be very careful not to change our plan or then we’re going to have to add all these benefits.

We also don’t know how it is going to affect our union employees. Our union plan is so rich that when the government plan goes into effect, anyone who has too expensive a plan will be fined, and the union plan meets that threshold. We’re not sure how that is going to work, because we’re not going to pay the fine for our union. That’s too big a benefit.

Some people think we’re going to get more business, because more people will have health-care coverage. The pricing of those benefits is probably going to have even more significant downward pressure on the pricing to keep it in line so the federal government can pay for it. We don’t know what that means.

This is going to be a very interesting transition for you.

It’s huge. Another big transition for this industry is what is happening with prescription drugs. The mid-’90s was a big decade for brand-name drugs. All these drugs with household names started in the ’90s. Prescription costs were just skyrocketing during this time. Then the last five or 10 years the generics have been taking over as the patents on these drugs expire. As the drug went from brand to generic, prices drop 80% on average. Our sales dollars of those prescriptions plummet 80%, and 85% of the market now is generics.

Also, there have not been that many new drugs coming on the market in the last few years. Most new drugs that have come out are very expensive specialty drugs that might cost someone thousands of dollars per month. They tend to be less stable so they’re often not in pill form; they’re more apt to be injectables or perhaps have to be refrigerated. Many of these are not available through a pharmacy, because of the special handling required. Some market participants might specialize in just one drug for one disease.

Another factor here is that for very, very expensive specialty drugs, the government is starting to require outcomes proof. If a manufacturer or a seller of a specialty drug is not able to satisfactorily prove the results in the patient, then the government might refuse to pay for it. Even if a doctor prescribes a drug, the drug won’t get paid for unless the doctor and the drug manufacturer can ensure patient outcomes. It’s just a whole new market. It’s not going to be the way we remember it.

Is this necessarily a bad thing? Isn’t this required to keep costs down?

We have all probably had a drug that the doctor said, “Well, why don’t you try this and we’ll see if it helps. If not we’ll try something else?” Well, the government doesn’t want to pay for those experiments. They want more assurance that it is going to work.

Moral Choices

What about dispensing pharmaceuticals that you don’t believe in? Is your business affected here as well?

A current issue is what’s called the Plan B drug, which is the morning-after pill, or the abortion pill, or whatever you want to call it. There are certain people who feel for religious reasons that they shouldn’t be required to dispense such a pill. That’s gone back and forth in this state. The Pharmaceutical Board at one point said that it could be at the discretion of the pharmacists. Washington’s Governor Chris Gregoire then told the Pharmacy Board, if they didn’t change their stance on that, she’d fire the whole board, forcing them to require all pharmacists to dispense the drug.

Then they said you could have the option of not doing it if there was somebody that you could refer the patient to. This led to a court case challenging whether a pharmacy could force a woman to drive 15 miles to another pharmacy, because you’re not willing to offer that service. The latest ruling says pharmacists should have a moral ability to say “no.” It’s gone back and forth so many times, but I think that’s the latest ruling. You can see we get caught in the middle of something between battling parties.

Fortunately, there are very few drugs that fit in this category. I supposed you could be against birth control, though I haven’t heard any of our pharmacists have an issue with that. If we did, I would assume that my pharmacy department would then just put that pharmacist in a busy pharmacy that has more than one pharmacist working at a time; then the one with the moral concern about that would not have to deal with it.

It would be harder for independents, where you might have only one pharmacist. It becomes an issue when the state can say what you have to do in this situation. I personally think that the state shouldn’t be able to say that. As a doctor, you don’t have to do an abortion. As a lawyer, you don’t have to take a case you don’t morally agree to take. Why shouldn’t the pharmacist be able to not prescribe a particular drug?

You run into even further problems when they say that a pharmacy is required to dispense all drugs, because we don’t have all drugs. There are some drugs that are so expensive and so infrequently prescribed that it would make no sense for us to have those in inventory. So we have to be allowed to manage our business in a businesslike fashion and in a moral fashion as we believe. Why is that woman’s right to access more important than our ability to manage our businesses as we want to?

Are there other examples of product choices you face?

We have people who don’t think we should have cigarettes anymore. That is a legacy business for a pharmacy. My grandfather would have had cigarettes back in 1900 so we have chosen to stay in the business. But we try to downplay it. The cigarettes are behind the counter and not visibly promoted. We are trying to treat people as adults who make their own choices. If you want to buy cigarettes, we have them available, because you’re used to coming to us for that product. But we’re going to make a bigger deal on smoking cessation products in our store.

There are some people who think we should not provide alcohol either.

Washington State Liquor Law

Have you expanded into other liquor now that the laws have changed? [Liquor other than wine and beer was available only in state-run liquor stores until a recent law change in the state of Washington.]

We are going down the road, because we think that people are going to expect us to have it. We’re going to have a pretty limited selection. This is such a weird thing for people in Washington state, because of the change.

It’s every day in California.

Yes, every grocery store and drugstore is offering this now. People are going to get jarred for a while, because it is new. But our emphasis will continue to be on wine. Washington state has a big wine industry, and we have specialized in Washington-state wine. We are the only retailer who emphasizes Washington wine. We feel like we’re supporting Washington-state business by doing that.

Advice

What advice would you have for young people coming into the job market in this time?

Find something you really like to do. Stay true to your own values and morals; no job is worth sacrificing those. Try to find a privately held company to work for!

Any other final reflections on your career at Bartell Drugstores?

It gets harder every year to do business. There are more regulations. It’s more competitive every year. You have to stay on top of many things from regulations to technology to consumer trends. There is a great deal happening on all fronts that affects our business, and so many like us around the nation. It is a constant challenge. But it is fun to serve a community and provide jobs to 1,700 people.