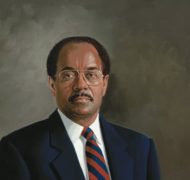

Faith and Public Policy: An Interview with William H. Gray, III

Blog / Produced by The High Calling

Rev. Gray didn’t leave the pulpit for Congress and politics, because he never left the pulpit.

William H. Gray, III, was the first African American to chair the House Budget Committee. He chaired the Democratic Caucus, and later, as Majority Whip, was the highest-ranking African American ever to serve in Congress. In 14 years as president of the United Negro College Fund, he raised $2.3 billion. During both tenures, he was pastor of Bright Hope Baptist Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In Washington, he was chief point man in budget negotiations between Congress and the Reagan administration. As special advisor to the President, he helped shape U.S. policy to restore democracy to Haiti. In 1995, he received the Medal of Honor from Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

He taught history and religion at five colleges—and has led the 5,000-member Bright Hope Baptist Church in Philadelphia for 35-plus years, like his father and grandfather before him. He received a master's degree in divinity from Drew Theological Seminary and a master's degree in theology in 1970 from Princeton Theological Seminary.

His many awards include the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Freedom of Worship Medal. Ebony Magazine named him one of the 100 "Most Important Blacks in the World in the 20th Century." He has also received more than 65 honorary degrees from America's leading colleges and universities.

Rev. Gray, for 13 years, you served in the U.S. Congress—five of them as head of the House Budget Committee. In 14 years as president of the United Negro College Fund, you raised a staggering $2.3 billion. All those years, you also pastored a church?

Yes, I did. I am pastor of Bright Hope Baptist Church in Philadelphia at the corner of 12th and Cecil B. Moore Ave., and I’ve been here 35 years as the minister of this church.

So you didn’t leave the pulpit for politics, because you never left the pulpit?

If anything, I just had a side trip into politics. I preached 38 to 40 Sundays a year while representing the second district of Pennsylvania. And I did the same thing when I went to UNCF. The other things I’m more well known for, but my real life is as a minister.

I am the third generation of Grays to pastor this church. For almost a century, they've had nothing but Grays. Rev. Comack founded it just before WWI and was pastor for about five years. Then right after the war, my grandfather was called here from a church in Richmond, Virginia. William H. Gray, Sr., passed in the late 1940s. In 1950, my father came to be the pastor until 1972 when he passed. And I was called in 1972. Four pastors in 95 years, and I have been the longest serving.

You come from a family of ministers and educators?

Before coming to this church, my father was president of a college for blacks. He had a master’s in chemistry from University of Pennsylvania. At age 21, he was a professor at Southern University where he met my mother. He earned his Ph.D. at Florida Memorial College and became president. Then he was called to Bright Hope Baptist Church.

My mother was from Baton Rouge. Her father was a professor of Greek at Southern University there. Her mother was a school teacher and became a principal at Scott Street School in Baton Rouge. The Yates were a big family; she had four siblings and they all went to college.

That’s a lot to live up to.

If you came home from school with a C, you got a whooping. You had problems with a B, but a C was punishment. Also, I come from a background of intellectual achievement and belief in education—a family that believed in a social contract with the community, that what is important is what you do for the community, not what you do for yourself.

Plenty of Christians consider politics dirty business, Rev. Gray. Others live as if political activity will usher in the new millennium.

I disagree strongly with both views. The business of government is how we create a community. And faith speaks clearly to how we create a beloved community where people can reach their possibilities and potentialities. Justice is the concretization of Christian love. Why, the Master always said, "When I was hungry, you fed me; when I was thirsty, you gave me drink." That determined whether or not you made it into the kingdom: in that you did it unto the least of these.

I find it interesting how people narrow their faith to one or two social issues. For me, participating in public policy is an opportunity to demonstrate the broad quest for justice that Jesus talked about. I’m informed by the entire Bible, but what’s critical is: what did The Master say? With whom did He associate? Who was He trying to raise—not just spiritually but physically?

So through politics, you . . .

As chair of the budget committee, I asked how are the least of these in our society being taken care of? President Reagan suggested cutting many school nutrition programs. He wanted to cut nutrition programs and make ketchup a vegetable. He wanted to eliminate the Pell Grant program that provides free grants to low-income students to go to college. Because I was chair of the budget committee, we said no, that program gives poor kids a chance to go to college and it’s means-adjusted; we had a federal standard of poverty. Your family could apply for a grant to go to college. That’s how my faith informed me as budget chair.

Do you tell people how to vote?

I tell them how I'm going to vote. People can make up their own minds. Sometimes they want to know how I'm going to vote, and I tell them the primary issue. I believe faith speaks to public policy issues and preachers have a role of being prophetic voices on the wall of judgment of man's machinations—man's policies that may not be correct.

I'd talk about an issue. I wouldn't tell them what to vote for. I talk about an issue and all the sides of the issue and faith, addressing how faith addresses that issue. What does faith say about that? Is there clarity about what faith says about that issue?

And if there is no clarity?

There's always tension in faith, a dialectic. It doesn't always clearly say Jesus would do X. It doesn't always provide simple answers to the complexities of life. You can find Christianity on two sides of an issue or four sides of an issue. It doesn't necessarily mean any are right or wrong but that's how they see it. I tell people to look at Jesus, the Christ, and what he would do and what he would say.

We have to use our faith, prayer, our judgment but always with a sense of humility, and not self-righteous, pharisaic thinking. Not with I'm right and you're wrong.

You grew up seeing Martin Luther King, Jr., across the family dining table?

Our families were friends; our fathers were dear friends. I knew him from the time I was five and he was 15. He used to come to our house on weekends for meals and worship at our church. He probably preached more at Bright Hope than any church other than the one he pastored. I knew him as an aspiring young minister.

Did knowing him affect you?

He symbolized what a minister could become in the issues of justice. So did my father. My father was involved in spiritual rights, so it showed me that you could have a critical role in the personal lives of people and bring about change in society.

People forget the U.S. government, not just individuals, was involved in racism. So the battle was against public policy. You couldn't go after it with the vote, so you marched across the bridge. You protested. You went to counters and sat. You integrated and got arrested because you couldn’t vote to change the laws. With all his education, my grandfather never had a chance to vote.

People forget that Civil Rights was a political movement conducted by people who did not have the ability to change the U.S. by the ballot. It was a political protest and also a religious protest movement. What did Martin Luther King oppose? Church folk.

Church folk?

Read Martin Luther King's letter from the Birmingham jail. Who's it addressed to? We've forgotten that he wrote a response to about 20 of the biggest white religious leaders of the South who called for him to spiritually reconcile himself and stop being a troublemaker. I'm talking about heads of the churches of the South. And his response has become a classic on Christian faith in an unjust world. They told him to shut up, go home, boy, and Jesus will save your soul.

Go back and dig out the sermons of some of the "great American preachers" of the 1920s, '30s, '40s, '50s—particularly in the South. Though, admittedly, some ministers took a different perspective.

Whites joined the movement—like Rev. James Reebe who was killed on the streets in North Carolina because of his protests. Ministers and non-blacks joined. But they were in the distinct minority. This was a political revolution, theological revolution, social revolution. Most white religious leaders in the U.S. supported segregation and institution. Go back to some of the biggest Christian leaders of the 1950s and try to find anything about segregation. The Civil Rights movement was also a theological revolution because of Martin Luther King. He challenged the accepted theological view of American society.

A lot of people confuse America with the Christian faith. How can you be God-fearing and enslave 20 percent of the population based on color? White national evangelists would go to a town and meet in Mississippi to talk about Christian salvation while at the same time they were lynching black folk and never condemned it or segregation or the violence of segregation. Emit Till would be my age today, and the white church said nothing about the slaughter. They said when we all get to heaven what a day of rejoicing that will be, so you Negroes wait for your robes. Now they've accepted integration and invite black folk to their churches. But the issue of justice in society is not part of that faith.

For me faith has to be wrapped up in the issue of justice. Wherever Jesus went, he addressed not only the spiritual needs but the justice needs.

They'd come to Mississippi and have a rally on temperance and never address the lynching two weeks before. You can't compartmentalize Christ. That's a Christ of culture—to use a Nehborian phrase—not just judging culture but molding religion into the culture. That's man's hubris, because we want theological justification for our evildoing and ungodly and un-Christian ways. If we can construct a theology . . . that's why the Civil Rights movement was so profound. It was a political movement, a social movement, and a theological movement.

White Christianity in this country gets criticized for ignoring the beam in our own eye.

We've come a mighty long way in my life. The fact that I could be elected majority whip, the number three leadership position of the Congress, by a predominantly white Congress, is a major step. I remember the day that no black could go to the University of Texas. Now I see Texas win the national football champ with a black quarterback and a lot of blacks on the team and in the stands—nonathletes who are good students. But at the same time, we have still some critical issues.

We still have to push for a just society of equal opportunity. Just because you stop the injustice doesn't mean the injustice goes away. You outlaw it today, but the effects and de facto practice may remain for generations. You must vigorously stamp it out and change process and procedures.

And Christians should be at the forefront?

Absolutely. How do you make concrete Christian love? Through justice in society. Justice is different from fairness. If there's been a great injustice, simply ending it doesn't bring about a just society.

We can eliminate the law. But if the practice persists, that's an injustice. That's the residue of injustice, which applies not just to race but anything we're talking about. How do we make concrete Christian love through justice in the society? It's an ongoing process, a struggle, always.